When I was in grad school taking courses in Constitutional history, we would argue. In one class on religion and the Constitution, my adversary made a point about the First Amendment being the most important amendment. The instructor, Tom Morris—the foremost authority on slave law in the Americas—interrupted: “the most important amendment to the Constitution is the Fourteenth.” There was no denying the authoritative tone. Both of us were confused, but one is often confused by one’s professors in grad school.

Of course, we eventually learned that Professor Morris was correct—and still is. The Fourteenth Amendment is indeed the most important change to our Constitution that We the People have ever made. Primarily, this is because of Section 1 of the Amendment, which one of the co-authors and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax referred to as “the gem of the Constitution.”* It secured for all Americans full citizenship, the protection of the Bill of Rights from infringement by the states, a fundamental right to due process, and equality for all before the law.

So imagine my surprise when I found that Phil Leigh, writing in the blog Emerging Civil War, had portrayed the Fourteenth Amendment as a cynical ploy by Radical Republicans in 1866 to ground the South under the heel of the federal government in order to secure power for its own agenda! This agenda was somewhat unclear, until I saw that the article also appears in the ultra-libertarian Abbeville Institute’s Abbeville Blog. Considering the nature of the Abbeville Institute, one can imagine: Republicans used black suffrage to create the über-state that Libertarians fear and loathe.

[Note: as of 8/12/14, Phil Leigh no longer writes for Emerging Civil War, and his posts have therefore been removed from that site. However, the article referred to in this post is still up at Abbeville Blog.]

Phil Leigh has written quite a few posts for the New York Times’ Disunion blog. I’m familiar with Leigh only because of an exchange he had with Brooks Simpson at Crossroads a while back regarding an article he also wrote for Emerging Civil War and Civil War Chat. Leigh’s article offered an economic interpretation for the war’s causes. Al Mackey at Student of the American Civil War demolished part of Leigh’s argument in the comments section. Then Brooks copied the article to Crossroads and took the rest of it apart. Leigh then answered Brooks’ critique. I felt like Brooks got the better of the exchange, for several reasons, but that’s another story. But since I was familiar with the name, it jumped out at me. What I found was a rather stunning example of the jerked-from-context polemic that’s all too common among Libertarians.

The Radical Republicans and Early Reconstruction

Leigh begins by outlining the terms for readmission President Andrew Johnson and his cabinet considered a month after Lincoln’s death. The terms for readmission, which reflected Lincoln’s moderate policies, were: “(1) ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, (2) repudiate Confederate debts, and (3) renounce the secession ordinances.” In addition, citizens who might have assisted the Confederacy would be required to take an oath to uphold the Constitution. But Johnson would require ex-Confederates—those of means or rank who had wholeheartedly backed the Confederacy—to apply for a presidential pardon.

Leigh establishes this moderate-sounding plan of reconciliation in order to contrast it with the merciless Radical Republicans like Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, who would not rest until the rebel states were reduced to vassalage. Apparently, considering the way Leigh breezily mentions the loyalty oath, the fact that Johnson had his own agenda is not worth mentioning. Johnson’s idea was to turn on the Radicals, whom he despised, isolate them from the Moderate Republicans, then reconcile these Moderates with Northern Democrats (Johnson himself had been a Democrat before the war) and Southern ex-Confederates, who would all be beholden to Johnson after his pardon removed their disenfranchisement. His goal was to realign the political system on him and create a new party—more moderate than the slavery-dependent Democratic Party, but much more conservative that the still-new Republican. But Johnson is not Leigh’s target here—Radical Republicans are.

Leigh then argues that Johnson’s moderate terms were actually pretty severe: $3 billion in slave-capital gone; all Confederate debts in the form of investments or money worthless. This indeed did much to impoverish the South. But Leigh ignores the point that it was not Johnson who “wiped out” capital invested in slaves—the Thirteenth Amendment did that. And what nation in history has ever honored the war debt of traitors who tried to destroy said nation? It also bears mentioning that this was Lincoln’s strategy when he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, stating that it would not go into effect until January 1, 1863. This was a clear message to the South: come back before New Years’ and all will be forgiven; come back after then, and you will lose your “peculiar institution” forever. But none of this is germane to Leigh, because he is after bigger game.

Johnson’s lenient terms compelled the former Confederate states to eagerly agree, and they established (if they hadn’t already) new state governments and conducted elections in order to get back into the national Congress. Leigh correctly states that “Republicans were shocked that many of the Southern elected representatives for the first post-war Congressional session in December 1865 were former Confederate leaders. In response the Republican controlled Congress refused to seat them.” Why? Because:

Republicans reasoned that if Congress seated such representatives Southerners might join forces with Northern Democrats thereby creating a coalition that could drive the ruling Party from power.

Well, sort of. The point about being driven from power is true, but one must understand what that would have meant: permanent vassalage for blacks.

And this is my point about context: for Leigh, the events and conditions that lead to the drafting and ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment happen in a vacuum of mere politics. Politics abounded, to be sure, but the context of these events was the legal fate of almost 4 million blacks in the South. Keep in mind that the Dred Scott decision–with Taney’s chilling opinion that blacks were “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect“–was still the law of the land. So this was not a pissing match over reapportionment or some such; this was, for most Radicals, a moral point of the highest order. And so the main point of Congress, which was controlled narrowly by Republicans in 1866, comfortably in 1867, was to define the legal and political status of blacks.

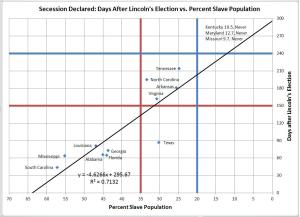

The reason the Republican Congress refused to seat these new Southern representatives (which was within their rights, according to the Constitution) was because their states had immediately began to oppress blacks and compel them to go back to the cotton fields whether blacks wanted to or not. After ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery, newly-freed blacks were in an anomalous position: they were free of bondage, but what else? What was to be their status? Were they to be “underlings” as Lincoln himself had worried in 1858? Almost as soon as it could, the new state government of Mississippi, realizing a desperate need for labor, passed the first of the Black Codes—laws intended to define the legal status of freedmen. The Black Codes were notoriously restrictive: while they did grudgingly grant blacks the right to own property, marry and move about, they curtailed other American rights severely. Blacks were not allowed to serve on juries, testify against whites in open court, or carry firearms. In short, the black codes–a kind of “slavery-lite”–established blacks as “underlings” under Dred Scott.

As reports filtered north that ex-Confederates were reestablishing the old social order of white supremacy and coerced labor, Radical Republicans and their moderate allies became impatient. They passed first the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which defined blacks as citizens; but then, fearing that this mere statute could easily be overturned (by exactly the coalition Leigh describes), they began to debate and craft another Constitutional amendment. This new amendment must do more than grant blacks citizenship: it must create a social order in which blacks could protect themselves from white Southern depredations. In other words, it wasn’t enough for blacks to have civic equality—they must have political equality as well. They must have the fundamental right to create a government which would protect their rights.

Black Suffrage as Republican Tool of Despotism

But this is context, and Leigh doesn’t go in for context, so there must be something else going on. And this leads us to Leigh’s big idea: that the Radical Republicans “settled on two objectives”:

First, was African-American suffrage in all former Confederate states. They expected that such a mostly illiterate and inexperienced electorate could be manipulated to consistently support Republican interests. Second, they wanted to disenfranchise those Southern Whites who were thought likely to oppose Republican policies .

The first thing to notice about this alleged “goal” is that it could be lifted straight from the Dunning School playbook. (Well, really Leigh’s entire article can, but this sentence is the bald-faced giveaway.) But whereas the racist Dunning School itself believed this statement wholeheartedly, Leigh qualifies it with “they expected,” meaning that it was the Radical Republicans who held blacks in racist contempt.

Why did Radicals keep Southern states in limbo and pursue a policy of black suffrage? Before fully discussing this, Leigh takes a right-turn tangent into the historiography of Reconstruction. He does so in order to take a swipe at modern scholarship. In doing so, I fear he tells us more about himself than modern scholars:

Over the last fifty years historians have largely reinterpreted Republican motivations. Shortly before the Civil War Centennial it was generally agreed the chief aim was to insure Republican control of the Federal government by creating a reliably Republican voting block in the South for which improved racial equality was a convenient byproduct. However, by the Sesquicentennial it became the accepted dogma that Republicans were predominantly driven by altruism untainted by anything more than negligible self-interest.

There are two points to make here.

First is the idea that historians are ideologically driven: that they are, in essence, a kind of arch-polemicist. More than mere pedestrian-level polemicists, since their research methods tend to be superior to non-historians, and their positions in university ivory towers make their opinions more believable. But, in the end, because of their adherence to “dogma” and ideology, the mere opinions of historians are no better or worse than anyone else’s. This is particularly convenient because once this notion is established, then Leigh doesn’t have to tackle some annoyingly large books to figure out what was going on. After all, if Eric Foner is a leftist, then who needs to read his essential Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877?

The second point has to do with the subject itself. It is the notion that this narrative that historians have constructed—that Republicans were driven to provide blacks with the suffrage largely by altruism—is a fantasy; that there is no altruism but pure greed for power. Here, Leigh is using the argument held by Progressive-era historians, like Charles Beard, who believed high-falutin’ notions of selflessness merely disguised more material motives and concerns. Radical Republicans cared not for black equality, but for power. Leigh’s doubts about altruism say much more about the Libertarian worldview than they do about Radical Republicans. Leigh’s disbelief in altruism seems to me a form of projection: because he can’t understand altruism, he can’t imagine its existence in others—least of all, crusty old guys like Thaddeus Stevens.

The second goal of Republicans, very closely related to the first, was indeed to disenfranchise ex-Confederates. Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment would revoke the notorious three-fifths clause. Blacks, no longer slaves, would be counted as full persons for the purposes of representation. This, of course, threatened to work against Republicans, since counting blacks as full persons, and not three-fifths of a person, meant that the ex-rebel states would have even more representation in Congress than they had in the antebellum period. If former slaveholders resumed power in the South, then the new status of blacks could not be protected without direct intervention by the federal government. The Black Codes would become permanent, ensuring control of the labor supply, white supremacy, and black “underling” status.

This is the true “agenda” of Radical Republicans, then. Black equality required both the suffrage of blacks and the disenfranchisement of ex-Confederates. Only then could blacks ensure and maintain their own equality without constant intervention by the federal government.

Republicans Craft the 14th Amendment to Pursue Their Nefarious Scheme of Oppression

Leigh continues by showing how Radicals intended to get the franchise to blacks. Because voting rules were firmly in the sphere of states’ rights, Republicans had to find a way to get around this. The best way to guarantee black suffrage was to create a new amendment to the Constitution. But Leigh points out two problems with this Republican plan:

First, the requirement that three-fourths of the states ratify the amendment implied a legal contradiction. While Republicans would need at least some of the Southern states to ratify it, they did not recognize such state governments as lawful. Second, in reality many Northern states and Republicans objected to uniform Black suffrage. Instead, they wanted mandatory adoption in the Southern states while permitting the matter to remain a states right elsewhere because…well that’s different, see?

In other words, if Radicals considered the new state governments allowed by Johnson illegitimate—so much so that Congress had refused to seat those states’ representatives—how could such an illegitimate state ratify a Constitutional amendment? How could one count such a states’ vote in the ratification process? In addition, universal black suffrage was opposed in much of the North. And so, it would be necessary for Republicans to come up with a scheme that would force Southerners to accept black suffrage, but not Northerners.

Because Northerners were racists, too. That’s the next part of Leigh’s position: that Northerners either did not allow blacks the vote, or put much more strenuous conditions on that privilege. Here, Leigh uses a typical neo-Confederate deflection: the North’s racism makes anything it did as bad as the South. This tu quoque (“you too”), or appeal to hypocrisy fallacy is a favorite of neo-Confederates, although its less common among Libertarians. Nevertheless, it’s wrong in its essentials.

Now, there was indeed much in the way of ugly political wrangling over how to ensure suffrage for blacks in the South; there was a fair share of self-interested arguments. And Leigh is partially correct in his accusation of Northern racism. But he ignores the Big Picture. He neglects to tell the reader what Republicans’ “agenda” really was.

Finally, Leigh gets to his main point, which essentially why the Fourteenth Amendment is difficult to read in places:

Eventually Republicans settled on a plan to achieve their objectives. The initial step materialized as the Fourteenth Amendment. First, states refusing suffrage to male citizens of any race would have their Congressional and electoral representation cut by subtracting the number of members of the excluded race from the applicable state’s population. Thus, owing to their tiny Black populations the provision was inconsequential in Northern states. In contrast, Southern states might lose considerable representation. Paragon examples are Mississippi and South Carolina where Blacks represented over fifty percent of the population. Second, despite the fact that Congress considered their governments unlawful, all Southern states would be required to ratify the amendment before they could be readmitted into the Union. In short, the Republicans ignored the legal contradiction because…well, consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

Hardly inconsistent. First, here is the text of Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed.

This revoked the three-fifths clause. But here is the “encouragement” for Southern states to allow black suffrage. I will strikethrough the many qualifiers that tend to bog down readers:

But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Even with the omission for clarity, it still suffers from the legalistic phrasing. But for all that, the message was actually quite clear: If states refuse to allow any black men to vote, then they would all black numbers for the purpose of representation. Preventing suffrage, either directly or indirectly with bogus qualifications like intelligence tests, would lose all the numbers of “such persons” from the counting for representation in Congress.

Section 3, coupled with Section 2’s qualifying “except for participation in rebellion,” was intended to accomplish the second goal of Republicans:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

This is the famous “iron-clad oath”: one must be able to say “I never raised my hand against my country and the Constitution I swore to uphold” in order to participate in politics. This effectively disenfranchised ex-Confederates while allowing Southern Unionists to assert their political will. The free-labor, non-slaveholding yeomen farmers of the South, so long rendered powerless by the slavepower, would now be able to make the ex-rebel states into true republics, rather than the white supremacist oligarchies they had become. And note the “except for participation in rebellion.” Congress would itself decide which ex-Confederates were reconstructed enough to participate in state politics. These Unionists, partnered with the freedmen, were the hope of the Republican Party in the South.

And as far as Leigh’s contention that there was something illegal in forcing the ex-rebel states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment before re-admittance to the Union, Congress was merely fulfilling its Constitutional obligation under Article IV, Section 5, which reads in part:

The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government[.]

The electoral composition of Southern states before and during the war was anything but republican. A small number of slaveholding families effectively dominated the politics of the South in the antebellum period. Real representative government was a fiction. More important, in this new postbellum period, real representative government simply had to include blacks and Unionist whites. The requirement of ratification, then, was the method Congress chose to ensure republican government in the South.

One might become uncomfortably close to agreeing with Leigh if one looked at the situation from Leigh’s sterile universe, where context does not exist. But in the world described by the historical record, the necessity of disenfranchisement and forced ratification is clear. Congress had just heard testimony of the riot in July 30, 1866 New Orleans, which began when Unionist whites and black U.S. Army veterans convened as Republicans to discuss a new state constitution. The convention was attacked by whites, mostly former Confederate soldiers. 34 were killed, over a hundred injured. Attacks like this convinced Republicans that the ex-rebel states were still violent, even barbaric places were normal political discourse was impossible. Disenfranchisement and required ratification were essential to change this. But this historical background is white noise to Leigh. It does not fit his predetermined outcome.

Part of the problem with ascribing a Republican agenda to this period of Reconstruction is that Republicans had almost no idea what exactly they were going to do! Outside of guaranteeing rights to blacks, there was no real “plan” in early 1867. The record is filled with the impatience of newspapers and politicians over coming up with a program to counter Johnson’s obviously unacceptable plan. Republicans did finally settle on an idea, though. I suspect it’s what gives Libertarians bad dreams. Because, in fact, Republicans held two motives equally high: black citizenship and a new social order in the South based on Northern values of free labor and capitalism. If Moderate Republicans cared more about getting at the under-used resources of the cotton states than they did black civil rights, Radicals certainly were more worried about black equality. This quote by Radical George Julian conveys the fusion of both:

What these regions need, above all things, is not an easy and quick return to their forfeited rights in the Union, but government, the strong arm of power, outstretched from the central authority here in Washington, making it safe for the freedmen of the South, safe for her loyal white men, safe for emigrants from the Old World and from the northern States to go and dwell there; safe for northern capital and labor, northern energy and enterprise, and northern ideas to set up their habitation in peace, and thus found a Christian civilization and a living democracy amid the ruins of the past. That, sir, is what the country demands and the rebel power needs. [January 28th, 1867.]

So they did develop an agenda. But not until after the Fourteenth Amendment was already in the works.

Section 1: The Gem of the Constitution

But perhaps this is a good time to look at the most important part of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus far, Leigh’s entire argument is based on Sections 2 and 3—that within these sections is the Hidden Agenda of the Republican Party. As we have seen, the true purpose was to guarantee blacks the power to defend their new rights. But what were these new rights?

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 1 actually was designed with two interrelated goals in mind, just not the ones Leigh says. First (and foremost), it was to grant full citizenship to blacks; in doing so, it set United States citizenship over state citizenship. And second, it was intended to protect a citizen’s liberties by applying the Bill of Rights to the states–one’s “privileges or immunities”—including the right to bear arms so that blacks could protect themselves from white Southern terrorism. The explicit language “No State shall” represents a tectonic shift of power in American federalism. For the first time, the federal government would take responsibility for protecting the basic rights of all Americans, since it was clear that states could not be relied on to do that. Couple Section 1 with Section 5–“The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article”–and you’ve got a document perfectly calculated to send tremors of fear and loathing through Libertarians everywhere. It was a vast expansion of federal power, but power for the sake of liberty.

And, making its debut appearance in the Constitution, there is the word “equal”:

[N]or shall any State…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Declaration of Independence was perhaps not the first, but it was the most important, document to declare equality a condition of humankind. That revolutionary idea had troubled Americans, living as they were in a republic that countenanced slavery. Many Southerners simply denied it and said Jefferson was wrong. But in November of 1863, Abraham Lincoln—according to Garry Wills—essentially slipped an early draft of the Fourteenth Amendment under our door in the Gettysburg Address. He told Americans that freedom and equality were part and parcel of a “new birth of freedom,” and that both were inextricable parts of the American creed. It was the Radical Republicans that made the first real attempt at making Lincoln’s words part of the Constitution.

And so this all-important Revolutionary theme—equality—was enshrine at last in the Constitution. It is this that Libertarians from the Abbeville Institute would attack and tear down. But he cannot attack this directly–equality, while imperfect and under attack, turns out to be quite popular with Americans. And so Leigh is reduced to launching ad hominem attacks on Radical Republicans.

Leigh’s work also suffers from an incomplete idea of the purpose of establishing black enfranchisement/ex-Confederate disenfranchisement. It was to allow the Southern states, composed of Republicans, to draft new, pro-democratic, liberal constitutions. And these coalitions of freedmen, Southern Unionists (“scalawags”) and Northerners (“carpetbaggers”) constructed very progressive constitutions indeed–they established public education, abolished imprisonment for debt, reduced the numbers of capital crimes, and all had state bills of rights that emphasized equality. The new governments based on these constitutions were composed of blacks and whites; blacks were even elected to the U.S. Congress. And these governments certainly would have executed Leigh’s nefarious plan:

As a result the Republican agenda of high protective tariffs, Federal land donations to railroads, banking and currency regulations unfavorable to the South, and a laxity of government regulation for monopolistic businesses continued for generations

See? The Republican-enforced Fourteenth Amendment caused the South to become a “colony” of the North for years to come. The only problem with this thesis is that these Radical Republican governments were all gone by 1877, and therefore fairly incapable of carrying out schemes of oppression. It is true that for the few years they lasted they worked very hard to turn the Southern states into something that resembled the North. But their failure was less because of corruption or black incompetency (as the Dunning School maintained) as it was white supremacist violence. Terrorism, in spite of federal protection, finally undermined the new governments and intimidated voters. The “Redeemers” were able to get elected, and then stage another set of constitutional conventions, overthrowing the progressive documents, and reestablishing the old order.

And so goes the attempt to discredit the “gem of the Constitution,” the Fourteenth Amendment. This particular effort avoids the all-important Section 1—which is really the part you and I care about today—and attacks Sections 2 and 3, which is very creative. However, it’s still wrong. The antiseptic, airtight laboratory where Leigh conducts his thought experiments turn out to be poor places to practice the craft of history. I know Leigh is frustrated that historians appear to him to be the “gatekeepers” of Civil War memory, the arbiters of “True: and “Not True.” But he will have to learn some of the historians’ craft before polemics like this rock anyone’s world. Prof. Morris is still right.

*Note: to be clear, Colfax was specifically referring to the Privileges or Immunities clause of Section 1. I have taken that appellation out of context and applied it to the entire Amendment.

**H/T to Jarrett Ruminski at That Devil History for the idea of sardonic photo captions.

Select Bibliography:

Akhil Reed Amar, The American Constitution: a Biography.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877.

David H. Gans and Doug Kendall, “The Gem of the Constitution: The Text and History of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” The Constitution Accountability Center, 2008.

Benjamin Kendrick, Journal on the Joint Committee of Fifteen on Reconstruction, https://archive.org/stream/journaljointcom00recogoog#page/n0/mode/2up

Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg.